AI is changing our world, and humanity has welcomed this technology with excitement. It’s being integrated into nearly every part of life. But is artificial intelligence truly objective and neutral? We want to believe that machines are free from human prejudice and emotion. Yet we often overlook one thing – machines can only do what we teach them. What does it actually mean?

AI is everywhere today. Companies use AI to screen job applicants, banks use it to decide who gets a loan, and even police use it to choose who to monitor. And in all these cases, AI can be just as biased as the people who create and train it. AI is trained on labeled data. These images are marked with objects, text labeled as hateful or not, or resumes marked as qualified or unqualified. These labels are considered to be ground truth from which AI learns. But think again – these labels are created by people, and each brings their own opinions, assumptions, cultural views and, sometimes, biases.

So, AI bias is not only in the algorithm. It starts with the data we trust as ground truth. Every dataset is the result of intentional or unintentional human choices. The way we label data decides how AI sees the world. A single biased label can affect the whole system, reinforce stereotypes, silence certain voices, and turn human-in-the-loop bias into wrong AI decisions.

In this article, we will study how annotation bias happens and how we can make data labels fair.

What Is Annotation Bias?

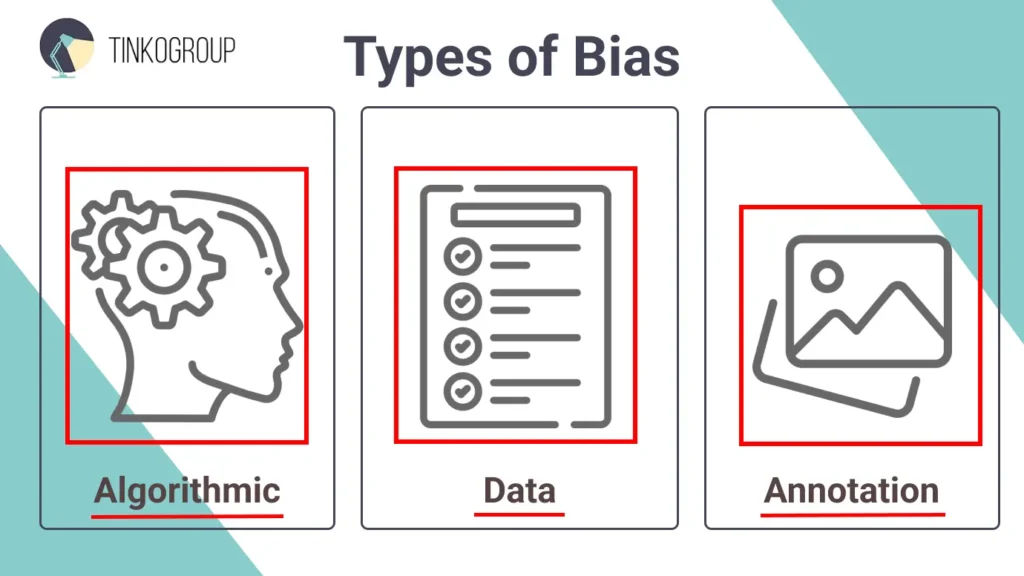

The term bias means different things in different fields. In psychology, it describes cognitive shortcuts that distort judgment. In statistics, it means systematic errors in data. But in artificial intelligence (AI), bias takes on a new form – unfair or skewed outcomes caused by flaws in data or algorithms.

- Algorithmic bias. It refers to the flaws in the model itself. For example, the model may give more importance to certain traits over others, even if that leads to biased decisions.

- Data bias. It’s the most common kind. It occurs when the data used to train AI doesn’t reflect the real world. If a hiring system is trained mostly on resumes from men, it may learn to favor male candidates, even if gender has nothing to do with job ability.

- Annotation bias. This kind of bias happens during labeling, when humans tag or describe data. If a person wrongly labels a smiling person of color as “not smiling,” or thinks a regional accent sounds negative, those mistakes get passed to the AI. The system then learns those wrong ideas and repeats them in its decisions.

We usually blame AI for algorithmic bias; however, a more hidden issue is annotation bias. Annotation bias is AI’s blind spot, which happens when human annotators, often unintentionally, assign labels that reflect personal prejudices or stereotypes.

AI bias was spotted back in the 1980s. One of the first known cases happened at St. George’s Hospital Medical School in London. They used a special admissions algorithm, which was found to unfairly reject women and non-European applicants. The system made decisions simply based on names and birthplaces. This case is not based purely on incorrectly labeled training data. Here, the system replicated human prejudice through hard-coded logic. However, the case set a precedent – automation can scale bias when human decisions are encoded into machines. Today, similar issues happen because of biased data labeling.

Many later studies have shown that poorly annotated datasets lead to discrimination errors. For example, in their 2018 Gender Shades study, Joy Buolamwini and Timnit Gebru analyzed commercial facial recognition systems and found that error rates were as high as 34.7% for darker-skinned women, compared to less than 1% for lighter-skinned men. It’s clear evidence that biased data annotation can directly harm people.

In the 2010s, AI moved into high-stakes domains like hiring, policing, and healthcare, and the real-world harm of annotation bias became undeniable.

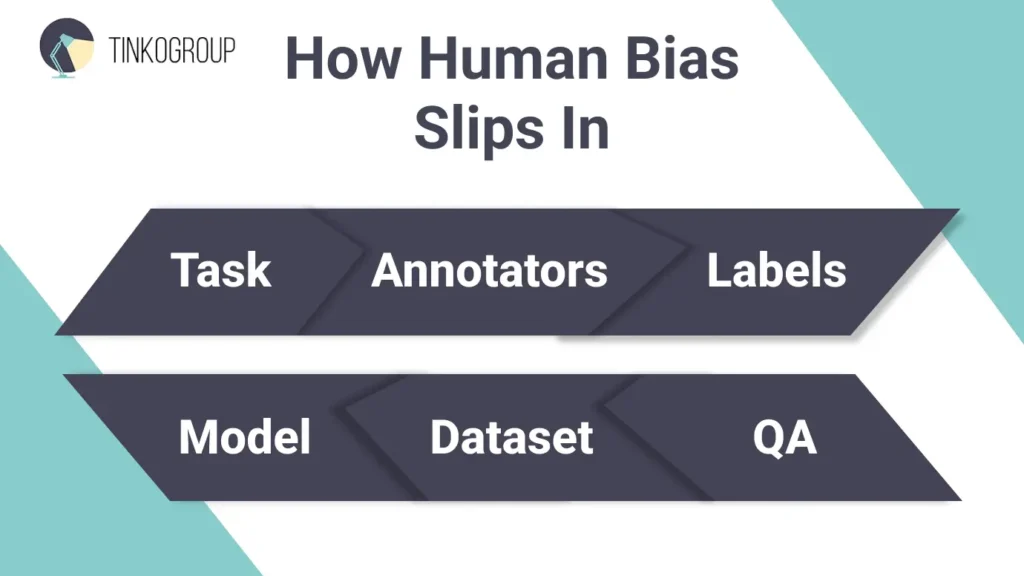

How Bias Slips in Through Cracks in the Pipeline

Annotation bias isn’t a technical glitch as many believe. Why? Because AI doesn’t just learn from data – it learns from the silent judgments of those who label it. And human bias in data annotation may have serious consequences.

Modern AI systems are large-scale and need a global workforce to label large amounts of data. It’s efficient, but also risky. Annotators often come from backgrounds that don’t reflect the users who will use a particular AI model. They label data based on their personal experiences, culture, or unconscious biases. AI models treat these labels as facts, and if a bias gets built into the system, it often gets amplified. Imagine how a teacher passes their own beliefs and knowledge to students over time. The AI training process looks the same, but annotators perform the role of the teacher. So, your AI is only as fair as its labels. And here is where bias most often creeps in:

Annotator Demographics and Experience

Labelers don’t interpret data in a vacuum – their culture, gender, education, and political views shape their judgments. Annotation work is often outsourced to a global crowd of workers for big projects, and usually, labelers come from regions with lower labor costs. This demographic disconnect is a fertile ground for bias.

A 2022 study by researchers at the Allen Institute for AI found that annotators’ personal political views and attitudes about race influenced how they labeled toxic language. It showed that annotators with more conservative views were more likely to label text written in African American English (AAE) as toxic, even when it wasn’t. At the same time, they were less likely to flag clearly harmful anti-Black language as toxic. As the authors put it:

“More conservative annotators and those who scored highly on our scale for racist beliefs were less likely to rate anti-Black language as toxic, but more likely to rate AAE as toxic.” – Annotators with Attitudes: How Annotator Beliefs And Identities Bias Toxic Language Detection.

This shows that bias doesn’t always come from bad intentions. It often comes from misunderstanding different cultures or ways of speaking. And when these kinds of judgments seep into training data, data annotation fairness is at stake.

Subjective Interpretation and Cognitive Bias

Even experienced annotators can interpret the same input differently depending on their assumptions. Human annotators introduce cognitive biases not because they’re poorly trained or malicious, but because cognitive shortcuts and social context influence their decisions. These lead to biased data annotation outcomes.

A 2024 study showed that social media texts, when decontextualized and stripped from their original environment, are highly vulnerable to mislabeling. It’s especially obvious when labeling is performed by annotators unfamiliar with the cultural norms of the original speakers.

“Cognitive biases originate from individuals’ own “subjective social reality” which is often a product of lived experiences. This makes cognitive bias a deviation from the rationality of judgement, therefore it may consist of perceptions of other people that are often illogical.” – Blind Spots and Biases: Exploring the Role of Annotator Cognitive Biases in NLP

This highlights a major blind spot – annotation without sufficient context encourages subjective readings that may not reflect the true intent.

Poor Task Instructions

If annotation guidelines are vague, contradictory, or culturally narrow, labelers will improvise. This opens the door to inconsistent or biased data. And it’s especially obvious in subjective tasks like detecting harm, intent, or sarcasm.

A 2022 study by M. Parmar shows that annotation instructions themselves can be a major source of bias. Annotators often mirror the wording, examples, and framing given in the task prompt. This is known as instruction bias.

“Annotators tend to learn from the instructions and replicate the patterns shown to them, even if they’re not representative of the data distribution.” – Don’t Blame the Annotator: Bias Already Starts in the Annotation Instructions.

If examples focus too heavily on one type of input, annotators label similar cases more often, even if that doesn’t match the real-world variety. As a result, models trained on this data may perform well on “instruction-shaped” patterns but fail on more diverse, natural language inputs.

Many platforms rely on majority vote to resolve annotation disagreements, but it can hide important perspectives, especially in tasks about hate speech or identity-based language.

A 2023 study by E.Fleisig showed that when annotators from the groups being discussed are included, models better understand the true meaning behind the language. The study found that simply following the majority often ignores how marginalized people interpret certain words or phrases.

“Modeling individual annotator perspectives, especially from the target group, improves prediction of both individual opinions and disagreement.” By paying attention to different opinions instead of just the majority, AI systems can become fairer and better at recognizing real context. This means disagreement among annotators isn’t just noise – it carries valuable information.” – When the Majority is Wrong: Leveraging Annotator Disagreement for Subjective Tasks

So, if, for example, slang or dialectal speech is unfamiliar to most annotators, the majority vote can incorrectly flag it as offensive, ignoring the way community members actually use it.

AI Bias Examples from the Real World

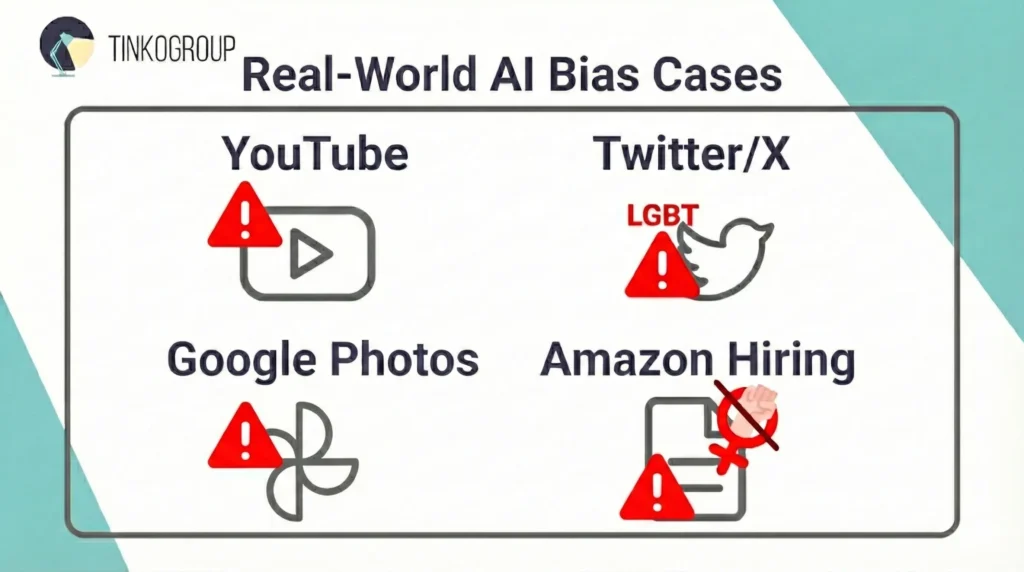

Unfortunately, annotation bias isn’t a theoretical concern confined to academic studies. It happens at scale in real-world AI systems. When left unchecked, these biases can cause serious harm by unfairly impacting people’s lives and voices. And here are some of the loudest cases where this has played out.

YouTube’s Hate Speech Moderation and African American English (AAE)

A few years ago, YouTube started to cause problems for creators who use African American English (AAE). People noticed that videos and comments with AAE were flagged or demonetized much more often, even when the content wasn’t harmful. This raised concerns about unfair treatment and bias.

The problem comes down to how the AI learns. It depends on data labeled by people who often don’t understand the cultural background of AAE. Many annotators come from different communities and interpret AAE words as aggressive or toxic when they’re not. This is worsened by systems that pick the majority label, which often reflects the dominant culture’s view, leaving minority voices unheard.

The results were painful. Black creators discovered that their content was blocked or hidden away for no reason. In 2020, a group of black YouTubers filed a federal class-action lawsuit claiming they earned less money, got fewer subscribers, and their videos were deleted because of YouTube’s racial bias.

YouTube has taken steps to reduce bias, but Black creators and people who speak African American English (AAE) still face unfair treatment. This AI bias shows up not only in moderation but also in how content is recommended. Black creators find it harder to get visibility and grow their audiences.

Google Photos Tagging Incident

In 2015, a shocking mistake happened with Google Photos. A software developer, Jacky Alciné, found that the application had labeled photos of him and his friend as “gorillas.” The error caused outrage worldwide and revealed serious problems of AI training data bias.

It was not a technical issue. It showed that Google’s training data didn’t include enough diverse examples, and annotators didn’t have the right guidance or background to label photos fairly. So, AI learned wrong associations between skin color and labels and made this offensive mistake.

Google quickly apologized and turned off the feature, but the damage was done. The incident became a serious warning for the tech world. The New York Times revealed Google’s training data had almost no dark-skinned faces, and labelers lacked diversity. Google disabled tags for primates entirely (a temporary workaround) and later revamped data collection.

It demonstrated how human biases sneak into AI through the data and annotations and pushed companies to rethink how they collect and label data.

Amazon’s AI Recruiting Tool

Amazon built an AI tool to help screen resumes faster, but in 2018, they had to stop using it. Reuters’ investigation found the AI was trained on 10 years of male-dominated tech hires and biased against women. The AI downgraded resumes that included words or experiences linked to women.

The tool learned from years of past hiring decisions – those that already favored men. So, the AI picked up those patterns and kept following them. Since the “labels” the AI learned from were based on old, biased choices, the tool reinforced gender discrimination.

Amazon stopped using the tool and admitted that their system was trained on biased data. This case made it clear that companies need to check not only the algorithms but the data and labeling behind them.

X’s (former Twitter) Hate Speech Detection

The platform introduced a system for identifying hate speech. However, this system struggled with the language used by LGBTQ+ communities. Many users found their tweets flagged or removed just because they used slang or reclaimed slurs common in their groups. And these tweets were not actually hateful.

This problem comes from annotation bias. Most annotators don’t have experience with LGBTQ+ culture or the meaning behind their language. A study by T. Davidson shows annotators mislabeled reclaimed LGBTQ+ terms as toxic 5 times more often than neutral ones. Annotators could simply mark unfamiliar words as offensive if they did not have clear instructions.

This attitude hurts LGBTQ+ users as they cannot express themselves.. In 2022, X (Twitter) changed its rules to better understand when slurs are used in a positive or reclaimed way. The company acknowledged its previous mistakes; however, further improvements are still needed.

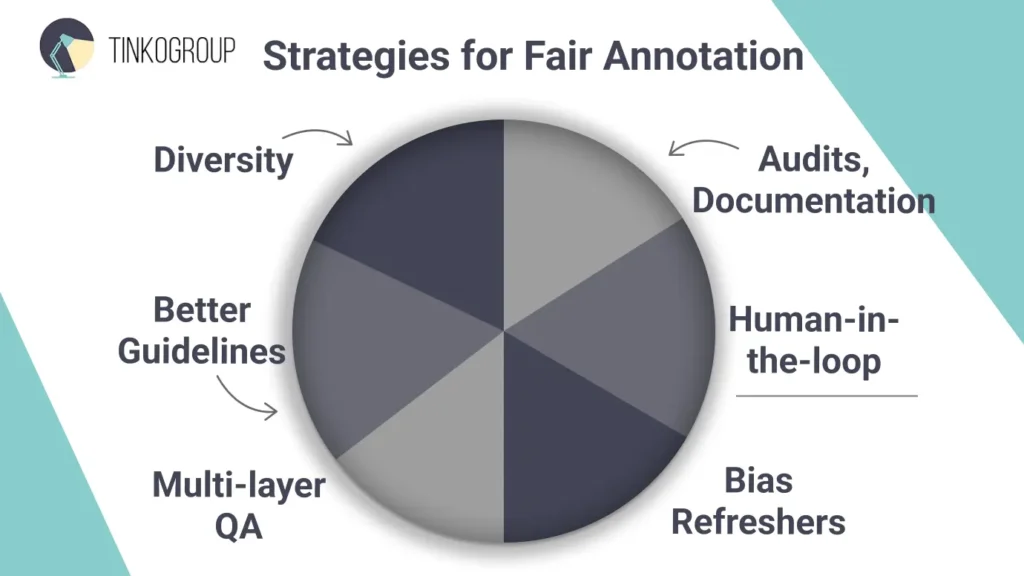

Strategies for Data Annotation Fairness

AI systems are trustworthy when they learn from trustworthy data. And this machine learning ground truth is made by humans. How to avoid annotation bias introduced by people during data labeling? It requires more than technical fixes. It demands intentional, human-centered design in annotation workflows. Below are seven strategies that make data annotation less skewed.

Annotator Diversity and Training

If your AI is learning from human-labeled data, then it matters who these humans are. When annotation teams all come from similar backgrounds – say, college-educated people from Western countries – you may get blind spots in your dataset. That’s because what seems “toxic,” “offensive,” or even just “correct” varies a lot in different people’s culture, identity, or lived experience.

So, diversity is not a trendy thing; it’s a guarantee of quality. A larger annotator pool captures different viewpoints and better reflects the audience your AI will serve. But even a mix of backgrounds isn’t enough. People also need guidance – clear training on cognitive biases, cultural context, and why their labeling decisions can have real-world consequences.

A 2023 study by J. Pei and D. Jurgens explains a lot. It analyzes the work of 1,400 annotators across the US and reveals that identity traits like race, gender, and education shaped how people labeled data. Even when the annotator pool was diverse, labels still varied in ways that reflected deeper social patterns.

Better Guidelines and Context Ambiguity can kill your annotation process. When instructions are vague or incomplete, annotators must rely on gut instinct. It often ends up with biased labels. Your annotation guidebook should be precise and clear:

- Define each label in detail.

- Include concrete examples of both correct and incorrect labeling.

- List edge cases explicitly.

- Provide cultural or domain context where needed.

A 2021 study by V. Pradhan, M. Schaekermann, and M. Lease introduced a three-stage “FIND‑RESOLVE‑LABEL” workflow for crowdsourced annotation.

- FIND – annotators should identify ambiguous examples under unclear instructions.

- RESOLVE – these edge cases are reviewed and clarified.

- LABEL – instructions are revised.

The result – instructions with clear examples and resolution of edge cases improved annotation quality considerably and reduced disagreement across annotators

Reliable Data Services Delivered By Experts

We help you scale faster by doing the data work right - the first time

Multi-Layer QA and Disagreement Resolution

High-quality data doesn’t come from a single review pass. It takes multiple layers of review to catch mistakes, bias, and misunderstandings. A layered QA system will help you identify disagreement, investigate it, and learn from it:

- Overlapping labels. Assign the same data point to multiple annotators. It will allow you to spot trouble early. When several annotators disagree, it’s a red flag something is wrong. These overlaps catch inconsistencies that one person might miss.

- Disagreement resolution. When annotators disagree, don’t settle it with a simple vote. Instead, send those tricky cases to a small team of experts or trained reviewers. Professionals will quickly figure out the true reason for the issue.

- Expert audits. From time to time, ask an outside expert with deep knowledge of the topic or culture to review some of the data. They can catch mistakes or biases your regular team may not recognize.

Audits and Bias Detection Tools

When you are watching for bias, you will be able to fix it. That’s why make a habit of treating bias like any other quality issue: something you track, measure, and fix.

You can use IBM’s AI Fairness 360 and Google’s Responsible AI Toolkit to check if your labels are skewed. For example, you can check if certain dialects or identities are flagged as toxic more often than others.

Once you know where the gaps are, set clear goals to close them. For instance: “Labels should be equally accurate for men and women, with no more than a 3% difference in error rate.”

Transparent Documentation

You should always be ready to clearly explain how your data is labeled and share the details of your data annotation process.

Good documentation should cover:

- Who the annotators are (their backgrounds, where they’re from).

- The guidelines they followed and how those guidelines were created.

- The quality checks and measurements used to keep labels accurate.

- Any known weaknesses or biases in the dataset.

This approach tells others where your data came from, spots possible bias, and lets them make smarter choices when using your AI.

Smart human-in-the-loop approach

Automation is great for its speed, but it can’t replace human judgment. That’s why you need human annotators who will handle tough moments. Let the machine deal with easy or repetitive things. Let AI pre-label data or flag examples that it finds ambiguous, and use humans where they are most needed. For example, people will handle emotion estimation tasks better than machines.

This hybrid setup does two big things:

- It saves time, because people don’t have to label everything from scratch.

- It improves quality because humans focus their attention where it really matters.

Ongoing Bias Refreshers

Your annotation guidelines cannot remain the same for long. Things that are considered harmful today may be called the norm tomorrow. You should review and update your labeling rules regularly. Maybe your team runs into edge cases that weren’t covered before, or new terms pop up in everyday language. Encourage annotators to speak up when something feels unclear or confusing.

It’s also good to run occasional bias refreshers. These don’t have to be formal or complicated. You may organize simple sessions to reflect your own experiences with annotation bias. We all have blind spots, and working with them is the first step to improving.

More advanced annotation teams turn these strategies into their ethical data annotation practices. This way, they create AI models that are not only more accurate but also more inclusive. It’s a smarter way to build systems that work better for everyone.

Conclusion

Fair and trustworthy AI starts long before any code is written. The biggest source of bias often comes from the way data is labeled and not from the algorithm itself, as it’s often believed. When human judgments in annotation go unchecked, they can turn into harmful patterns in AI systems. That’s why it’s so important to take data labeling seriously.

How do you achieve data annotation fairness? Use diverse teams, give clear instructions, and regularly check for annotation bias to get accurate labels. If you want AI to reflect the world fairly, you must treat the annotation process with care and responsibility. Ethical annotation means ethical AI.

At Tinkogroup, we help companies design bias-aware annotation workflows, build diverse annotation teams, and implement multi-layer quality control for high-risk AI systems.

If you want to ensure that your training data is accurate, representative, and ethically labeled, learn more about our services.

How is annotation bias different from algorithmic bias and data bias?

Annotation bias occurs during the data labeling stage, when human annotators assign labels based on their own experiences, cultural norms, or unconscious assumptions. Unlike algorithmic bias (which comes from model design) or data bias (which results from unrepresentative datasets), annotation bias is introduced before the model is trained and is often invisible. Because labels are treated as ground truth, even small biases at this stage can propagate and amplify unfair outcomes in AI systems.

Why is annotator diversity important for building fair AI?

When annotation teams share similar cultural or social backgrounds, they tend to interpret data in similar ways, creating blind spots. Diverse annotator teams—across culture, language, gender, and lived experience—are better equipped to recognize context, dialects, and community-specific language. This reduces the risk of minority speech, behavior, or identity being misclassified as harmful, abnormal, or low quality.

What practical steps can teams take to reduce annotation bias in real projects?

Reducing annotation bias requires a combination of clear and detailed labeling guidelines, multi-layer quality assurance, structured disagreement analysis, and regular audits for bias. Involving subject-matter experts and members of affected communities is especially important for subjective tasks such as toxicity or sentiment labeling. Rather than treating annotator disagreement as noise, teams should analyze it as valuable insight into ambiguity and cultural context.